- 01535 652338

- mail@watsonsbs.com

Lighting Design for Well-Being

Traditionally, lighting in the built environment has been designed, specified, and manufactured with a few key objectives in mind. The main goal has historically been to illuminate spaces effectively to enhance visual performance, focusing on aspects such as efficiency, productivity, and safety. Additionally, lighting has been intended to ensure visual comfort for occupants and to improve the aesthetic appeal of a space.

As energy demands and costs have risen, energy conservation has become an important consideration in lighting design, with sustainability at the forefront of any new build or retrofit. With the advent of LED lighting, technology has rapidly evolved and driven sustainability to a point where it is so efficient, that any further gains are minimal compared to when they were first introduced. That is all not to say gains cannot be made, and it is within the field of human-centric lighting design that lighting in the built environment will make the next big steps.

What Is Human-Centric Lighting?

The concept isn’t especially new, with the term coming into use over the last decade and lighting design already incorporating its methods. LightingEurope, a trade association based in Brussels, recently predicted that human-centric lighting will establish itself as the leading sector of the lighting industry by 2025.

Human-centric lighting technology focuses on designing lighting systems that enhance human well-being, productivity, and comfort by mimicking natural light patterns and adapting to the needs of individuals. Recent advancements in this field and its integration into building services include:

Circadian Lighting Systems

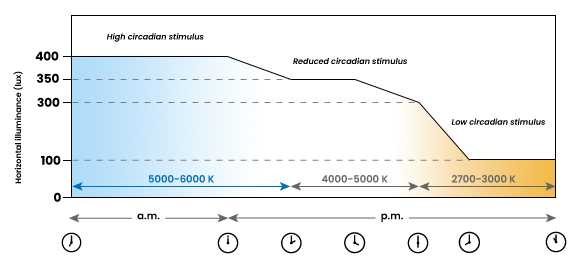

Circadian lighting systems are designed to support human biological rhythms. These systems use dynamic lighting controls to change light intensity and colour temperature, promoting alertness during the day and relaxation in the evening. Integration with building automation systems ensures seamless adjustments based on time of day and occupancy. The colour temperature from light sources is measured in Kelvins (K), with morning light mimicking a clear sunny day at 5,000 - 6,000K. A warmer colour at 4,000 - 5,000K is more representative of the afternoon sun, traditionally produced by fluorescent lamps, finishing with much warmer, low-intensity lighting at 2,700 - 3,000K representing sunset and usually achieved with low-energy bulbs and lamps.

The Circadian Lighting System Daily Timeline

By using these varying lighting temperatures to synchronise with the human circadian rhythm, regular occupants can benefit from enhanced mood and mental health, along with better physical health stemming from a more natural sleep pattern. However, there is no one-size-fits-all solution as some buildings have unique challenges. Hospitals, for instance, need to be lit enough at night for medical staff to remain alert and perform standard and emergency procedures on the wards. Unfortunately, this would mean a loss of healthy light exposure for both themselves and their patients. In these cases, specialised and tailored lighting design can support patient recovery and staff well-being.

Biophilic Design

This approach connects occupants with nature, reducing stress and promoting well-being. Views of nature and access to natural light have been shown to improve mood and cognitive function.

The term “Biophilia” was first introduced by psychoanalyst Erich Fromm in 1973, stating that it was the “passionate love of life and of all that is alive”. Although relatively new, elements of Biophilic design can be traced back as far as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Features that characterise Biophilic design can be seen throughout preceding sustainable guidelines, but the creation of a framework in the 1980s by Stephen Kellert brought the term and the concept to the forefront of building design.

|

Principle |

Direct experience of nature |

Indirect experience of nature |

Experience of space and place |

|

Outline |

Tangible contact with natural features |

Contact with images and or representations of nature |

Uses spatial relationships to enhance well-being |

|

Examples |

Natural light, natural air sources, water features, plant life, observable weather |

Images of nature, natural materials, earth tones, simulated light and air |

Transitional spaces, breakout areas, private areas |

Incorporating elements of natural light into indoor spaces through windows, skylights, and daylighting strategies is a key aspect of biophilic design. Exposure to natural light provides many health and mood benefits, including increased production of vitamin D, which is essential for bone health and immune function. Removing the dependency on artificial light promotes well-being through healthier indoor environments.

Where there is sufficient natural light to illuminate a room, lighting can be switched off via sensors connected to an automated control system. This is in the same vein as monitoring a room for occupancy and switching off energy-consuming functions when rooms are unoccupied, and integration with a building’s BMS with smart control pushes sustainability forward.

Integration into Building Management Services (BMS)

When integrating human-centric lighting into buildings, Watsons follows an important process to ensure the building or space works the way it is intended:

Assessment and Planning: We evaluate the specific lighting needs of the building’s occupants and spaces, considering factors such as natural light availability, occupancy patterns, and desired outcomes.

System Design: We develop a lighting design that incorporates human-centric principles. This includes selecting appropriate fixtures, controls, and sensors, as well as planning for integration with existing building management systems.

Implementation: Install and commission the system, ensuring it is properly calibrated and programmed to deliver the desired lighting conditions. Integration with building automation systems is crucial for seamless operation.

Monitoring and Maintenance: We provide training to building staff to monitor the system’s performance and make adjustments as needed. Planned maintenance ensures the system operates efficiently and continues to meet the needs of occupants.

Case Study: Refurbishment of a 30,000ft² Office Building

Watsons undertook a major refurbishment project, designing and implementing the mechanical and electrical services for a large office building situated in Bradford City Centre. With most of the existing infrastructure dating back to the 1980s, it was a fantastic opportunity to bring a large building up to date with significant cost-effective and sustainable upgrades.

Among the major upgrades was a complete overhaul of the lighting system, incorporating energy-efficient LED lighting on each of the seven floors across the two wings of the building. The lighting was designed and installed to enhance the well-being of the occupants, and Biophilic design principles were introduced where natural light sources were sufficient to reduce dependency on artificial light.

The significance of lighting design in promoting occupant health and well-being cannot be overstated. By considering factors such as circadian rhythm regulation, mood enhancement, visual comfort, productivity, physical health, social interaction, biophilic design, personalisation, energy efficiency, and specialised applications, lighting designers can create environments that support and enhance the health and well-being of occupants.

Investing in thoughtful lighting design is an essential component of creating healthier, more productive, and more enjoyable spaces for people to live, work, and thrive in. Visit our Electrical Solutions page and find out more about how Watsons can help improve your building’s energy efficiency and occupant well-being.